MOVIE REVIEW: The Dutchman

THE DUTCHMAN— 2 STARS

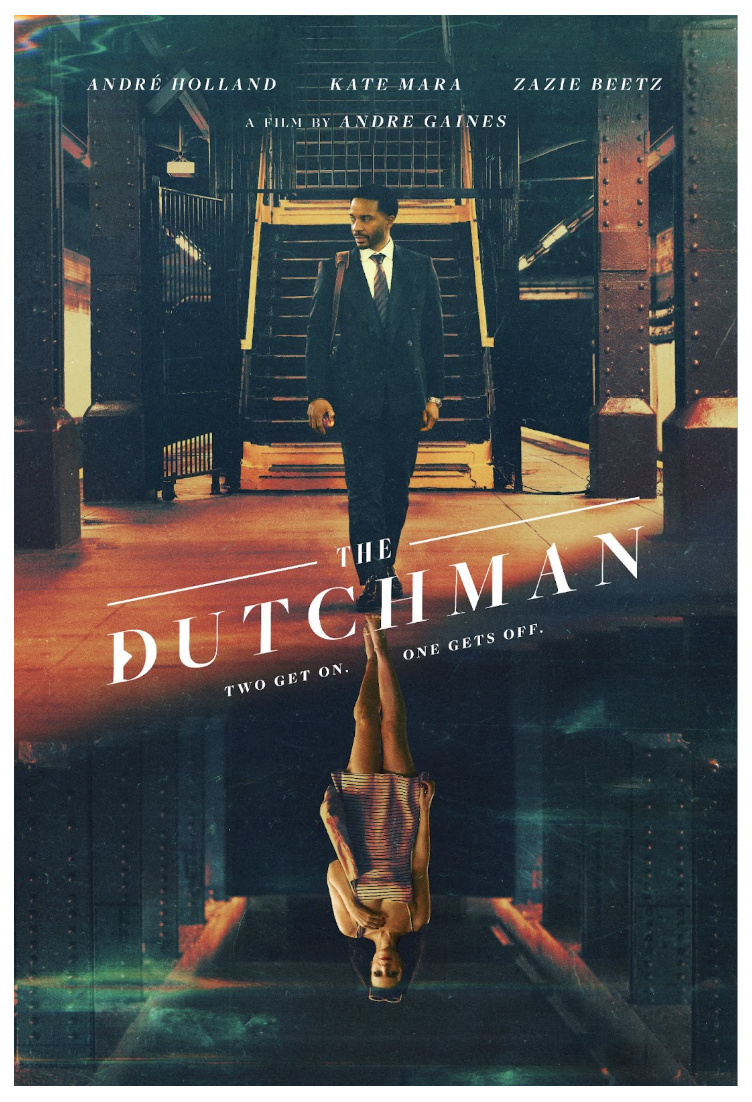

Stepping into 2026, it is remarkable to examine how many films in this day and age “go meta,” so to speak. Being self-referential is often seen as a reward for prior knowledge placed for those apparently savvy and educated viewers. Audiences want to feel smart and in on the joke, and that plays well in comedies and comic book movies. That’s not necessarily the case for dramatic stage plays. Imagine Erik from The Phantom of the Opera or Troy Maxson from Fences figuratively giving their audiences a knowing gesture, acknowledging that they’re on stage and not truly in their setting. It would destroy tension and focus. The 2025 film adaptation of Amiri Baraka’s celebrated drama, The Dutchman, by successful documentarian Andre Gaines in his feature film directorial debut, makes the grievous mistake of “going meta.”

After an ominous voiceover by stellar veteran character actor Stephen McKinley Henderson of Civil War speaking about “two warring ideas in one dark body” and how “lost” our main character is—showing us the future yet to come in the movie, this take on The Dutchman opens on a married couple, Clay and Kaya (Andre Holland of Exhibiting Forgiveness and The Harder They Fall’s Zazie Beetz, stuck in "movie wife" mode), sitting in a couples counseling session. They sit apart on a couch, and neither is committing to much eye contact with the other. You can cut the contentiousness with a knife. We learn that Kaya recently had an extramarital affair, an act that Clay has staunchly not coped with or forgiven. It eats at his heart and dignity, which has infected his hectic work assisting the political campaign of Harlem public figure Warren Enright (an underused Aldis Hodge of One Night in Miami…). Kaya, the unfortunate benefactor of an overstretched husband, would love to talk about all of it, but runs into Clay’s stone wall of pride.

The therapist, Dr. Amiri (the first meta wink and played by Henderson), pivots away from the errors of Kaya to target the current contemptuousness of Clay. Clay expounds on his journey as a Black man climbing the ladders of success and acceptance. The doctor posits whether it would be better if Clay had his own chance at infidelity to settle the proverbial score. Little of this counterargument registers with Clay as he continues to point to the importance of his career and the singularity of the error occurring with Kaya and not himself.

Before departing the session after Kaya exits, Dr. Amiri pulls Clay aside to continue the questions about feeling divided and unbalanced when it comes to conformity, anger, respect, vulnerability, and more—all heady questions fitting of the overarching mindset. He asks Clay if he’s ever heard of Dutchman and offers a libretto copy of the script. He assumes that Clay, an educated Black man (like Holland himself), knows the story of a man confronted by evil incarnate on a train, and wonders if Clay is that man now. Venturing further in the blunt acknowledgment department, the camera shows Clay’s attention captured by a lone pewter figurine of a man standing next to a small tabletop model of a well-adorned theater stage.

LESSON #1: DON’T TELL YOUR MAIN CHARACTER EXACTLY WHAT’S GOING TO HAPPEN— By introducing the pre-existing premise of the play in a self-referring way, this is precisely where The Dutchman falters. When the scandalous events of Amiri Baraka’s drama occur to our Clay—and they do, as he encounters the flirtatious white temptress Lula (Kate Mara, recently seen in Friendship) on a subway train—it feels like the main character should have been able to know all of the signs and pitfalls before him because they match the exact warning and reference he received. Once Lula threatens to expose the evidence of their transgression to his wife, Warren, and his constituents unless Clay brings her to a campaign party, our protagonist’s alleged wisdom erodes further.

LESSON #2: OVERDOING SYMBOLISM— Alas, the extravagant meta angles of Gaines’s The Dutchman are not done. To see Stephen McKinley Henderson’s doctor and that figurine stage continue to appear in more settings and guises, the oddity of it all grows as we wonder if Dr. Amiri and Lula are in cahoots to execute this internal tailspin for Clay or a larger, destructive descent. The intention of adding this illusory depth and puppeteering suggestion and giving it all the foreboding tone possible by the musical score from The Green Knight composer Daniel Hart, akin to Al Pacino’s grandly elemental presence in 1997’s The Devil’s Advocate, counts as bold, but is poorly executed. Rather, this is flatly overdoing symbolism and causes wild confusion.

One of the challenges in adapting theatrical plays into films is matching the intimacy and intensity that come from the stage setting. There’s something about how every movement and emotion is confined under the stoplight for all to see, and how the minimalist sets are meant to be a thin container, not an enveloping presence. Once a story is taken away from that container and expanded to location shooting and more immersive production design, the style quotient certainly goes up, but the aforementioned intimacy and intensity can be diluted. Andre Gaines and his screenwriting partner, Qasim Basir of the Sundance favorite To Live and Die and Live, overwhelm these traits of The Dutchman.

The plot of Amiri Baraka’s Obie Award-winning one-act play never leaves the fateful subway car where the indignant Clay intersects with the predatory force of Lula. Pitting competing temptations against each other, the two trade lengthy diatribes that lay bare racial stereotyping, Black identity, and cultural appropriation. Created and set during the mid-1960s at the height of the Civil Rights Movement—and seen once on film in 1967 with Shirley Knight and Al Freeman Jr from The Lion in Winter director Anthony Harvey, the rhetorical counterattacks in Dutchman threaten to turn sexual and violent, building a massive amount of dangerous agitation matching that tumultuous era.

LESSON #3: STICK TO THE CORE SOURCE— The thing is, though, there’s little to nothing outdated about that premise. That same clash of weaponized racist ideology could occur today, 60 years later, on the same New York City subway system with cell phones and other modern trappings, and still create the kind of powder keg acting the original Dutchman manifested to strong success. As soon as Gaines goes meta with the planted existence of the play and the weird angle of using it as some kind of creepy curse hanging over Clay, the core source is radically changed and rendered almost rootless to what occurs.

It’s a shame because the potential was all there with the combination of Andre Holland and Kate Mara. The accomplished actors melt into each other’s magma with their verbal battle and escalating body language. The reenacted subway confrontation of The Dutchman precariously hinges on “will they” or “won’t they.” When Holland and Mara let loose with their manipulative monologues and caustic responses to each other, which surge with all the hot take sociopolitical commentary one hopes for, the suspense is exceptional. However, the inertia is severed by the swerves chosen by Gaines and Basir to veer towards the wholly unnecessary middle section of marital extortion and the sinful bedroom of sexual revenge. The performers did not deserve to be yanked around and overstretched. Their acting almost saves the film, but only so much.

Less would have been more, and less was already enough with The Dutchman. The movie never had to leave the train or the topics unleashed there. The originally intended inescapable struggle is demystified the moment it treads away from it. Worse, by leaving and constantly pointing at the fact that the very theatrical setting exists and supposedly still looms large, it negates what made it powerful and great in the first place.

LOGO DESIGNED BY MEENTS ILLUSTRATED (#1364)