MOVIE REVIEW: A Haunting in Venice

A HAUNTING IN VENICE— 3 STARS

Even giants of literature like Agatha Christie have a dud or two on their celebrated vitae. Agatha’s later-career effort of Hallowe’en Party from 1969 is one of them. Literary critics at the time called it “weary” and a “disappointment,” among other dismissive criticisms. Time has softened a large portion of that negative reception, but, even so, there’s a temptation of resting on the notion of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” when it comes to adapting work from a certified classic author like Christie into a feature film. Call it laurel-resting cruise control.

That, my good folks, was never going to happen with Academy Award winner Kenneth Branagh at the helm. As deeply reverent as he has long been to the works of William Shakespeare and Agatha Christie across his sensational career as an actor and filmmaker, Branagh is his own gilded and celebrated artist. With A Haunting in Venice, he and Logan screenwriter Michael Green have taken a meandering, humdrum book with a drab surroundings and loose ends and given it style and sizzle, as only they can.

A Haunting in Venice takes place in 1947, ten years after Death on the Nile’s 1937 setting, and makes a pair of contrasting opening statements. From one place of tone, we hear Vera Lynn’s rendition of “When the Lights Go On Again” playing while the familiar coastal urban geography of Venice, Italy is introduced on camera. It paints the post-World War II hope of the era and keeps things appealing and serene. That swanky ease is broken when a seagull dives into a sidewalk flock of pigeons and gobbles up a feathery meal with an ear-splitting shriek. At the same moment, Joker composer Hildur Guðnadóttir’s eerie musical score arrives to sting a few bars while rain turns the picturesque sights underneath wet and dingy.

Right then and there, A Haunting in Venice presents its parallel aim of punctuating and smearing old decadence with unexpected violence, and we are there for it. Famed investigator Hercule Poirot (Branagh) is trying to enjoy retirement with a visit to the City of Water only to be hounded by eager potential clients with cases to solve. His hired security detail, former local policeman Vitale Portfoglio (John Wick: Chapter 2 villain Riccardo Scamarcio), dispatches most away, but grants one an audience. That lucky pass is granted to mystery novelist Ariadne Oliver (nine-time Emmy winner Tina Fey), slinging her “flim-flam” gusto to turn phrases and twisting her old friend’s arm.

Oliver nudges Poirot to join her as a guest at socialite Rowena Drake’s (Yellowstone star Kelly Reilly) Halloween party at a supposedly haunted palazzo that used to house unclaimed orphan children, many of which died there. The main attraction at this gathering is a notorious spiritual medium named Joyce Reynolds (Everything Everywhere All at Once Oscar winner Michelle Yeoh) hired by Rowena to commune with her deceased daughter Alicia who died at the palazzo the year before in suspicious circumstances. Also assembled for this invitation-only seance are the family doctor Leslie Ferrier and his young son Leopold (Branagh’s reunited Belfast duo of Jamie Dornan and Jude Hill), the Drakes’ longtime caretaker Olga Seminoff (Camille Cottin from Sweetwater), and Alicia’s former flame Maxime Gerard (Kyle Allen of The Map of Tiny Perfect Things).

LESSON #1: ANYTHING NOTICEABLE IS WORTH REMEMBERING– Though Ariadne claims Poirot is there to help her discredit Joyce Reynolds, the very logical Hercule suspects she– and others– are up to something. Even as a gracious guest in Rowena’s home, his antennae are always on. To quote a line from Christie’s source novel, “Anything noticeable is worth remembering,” and few things get past our hero. Naturally, the film is here to challenge its viewers to do the same at every turn.

LESSON #2: WHAT WOULD MAKE YOU BELIEVE– While Poirot entertains a child-like curiosity to bob for apples leftover from the party after the clock strikes midnight, someone tries to drown the mustachioed Belgian doyen. Soon after, one of the party’s attendees is found murdered. Because of the seance, some survivors jump straight to fears of, shall we say, spectral infiltration as the chief culprit. Our old sleuth will have none of that spooky nonsense. Sure enough, the clues point to an old murder being the motivational key to this new one. Yet, the logically-minded and analytical Poirot stomps on the after-death debate with fervent opposition and rank disbelief, only to find himself jaded after continuously seeing and hearing things that do not match his rational thinking.

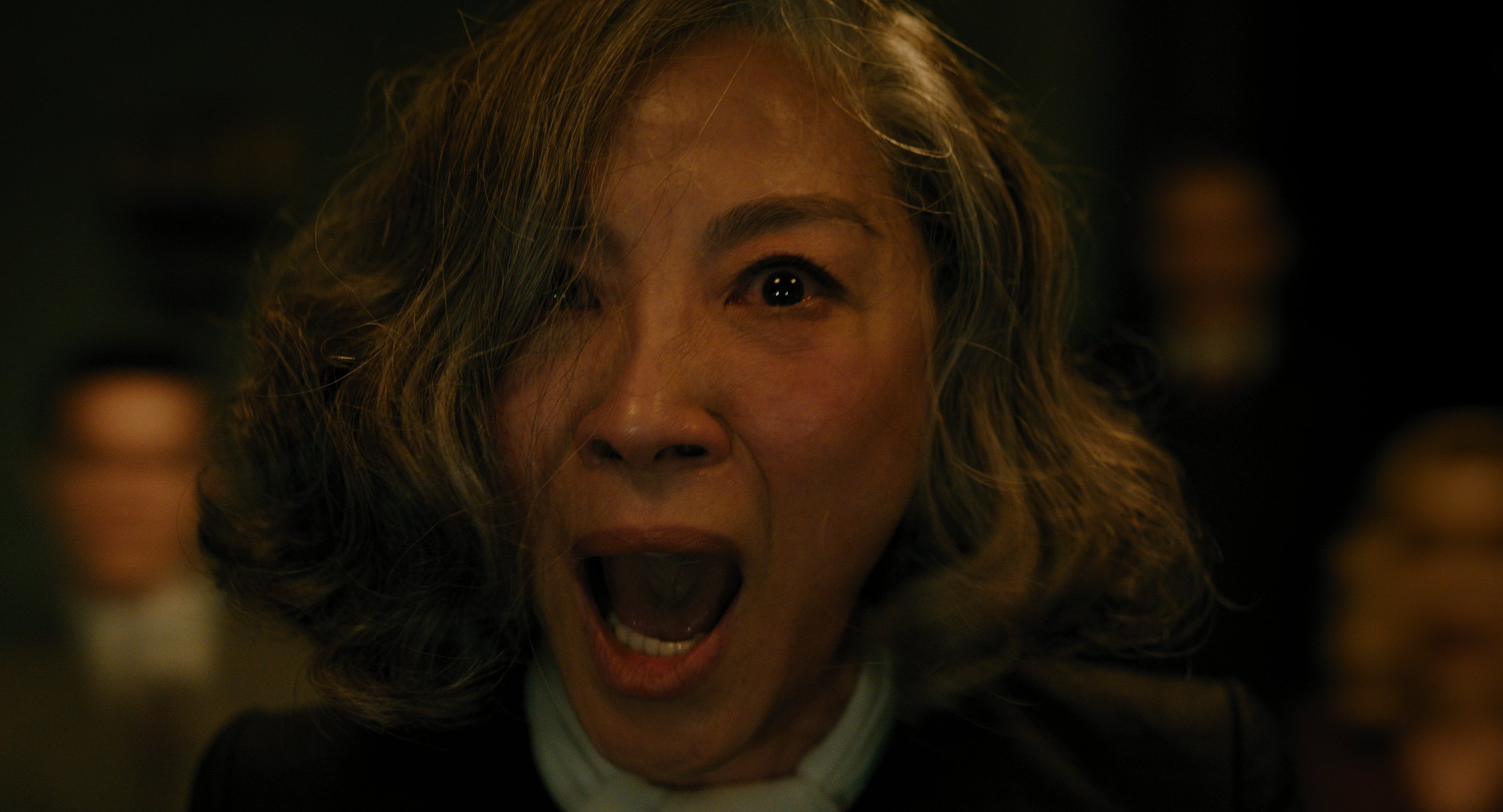

Naturally, no one is a clear villain and everyone is a suspect, allowing the A Haunting in Venice cast to flex amounts of ambiguity found in their characters. Michelle Yeoh is a jolt of stoic and exotic intrigue, while Tina Fey was ideal casting for pumping up the witty repartee. Outside of a PTSD distinction and Jude Hill holding his hand with put-upon creepy maturity, Jamie Dornan, for his billing, is disappointingly flat. However, young Kyle Allen pops off the screen with an indignant spunk as the jilted man-about-town stuck answering for old mistakes. He leaves possibly the most solid impression of the cast.

Of course, though, this is still Kenneth Branagh’s schtick and show. The actor’s third big screen take on Hercule Poirot continues to be very magnetic. Beyond the eye-catching and memorable facial hair, Branagh’s dignified posture and perfectly creased body language command instant screen presence. Kenneth constantly lifts his fellow actors to rise to the confrontational occasion of his inquisitive character and his level as a gifted performer.

Compared to Christie’s Hallowe’en Party, Branagh and Green wisely employed addition by subtraction to make a more cohesive and entertaining film. A Haunting in Venice trades suburban London for lush expat Venice, giving the setting flashier grandeur. Similarly, the keen screenplay reduces the number of characters, locks everything into this estate setting, and sets its countdown timer for resolution to a single stormy night, eliminating Hallowe’en Party’s long and drawn-out investigation timeline and rudderless backstory. All in all, Branagh appreciably threads this diabolical web in under two hours.

LESSON #3: MAKE IT ALL SCARIER– Any murder, at its garden variety face value, should be frightening enough, but A Haunting in Venice twists the knife further. Narrative and cinematic infusions of supernatural elements and implications not found in Hallowe’en Party are the film’s largest dramatic improvement from the source text. They turn what would merely be posh and intriguing in an ordeal far scarier in design and risk. Starting with that munched bird cold open and developing later with hallucinations of ghostly imagery, there is an unmistakable level of extra bite and edge.

Once again, Hildur Guðnadóttir’s darker style of score– over the more sumptuous work from Branagh’s usual collaborator Patrick Doyle– plays into that purposefully amplified mood. Returning Poirot series cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos adds to the disillusionment goal with stretched wide lens views that would make Yorgos Lanthimos proud and a bevy of Branagh’s signature Dutch angle establishing shots that hammer home the askewness. While A Haunting in Venice is not an outright gothic horror film emptying a bloodbank’s worth of crimson everywhere, the polish is too good to deny and the chilling level of suspense with these extra traits is more than sound.

LOGO DESIGNED BY MEENTS ILLUSTRATED (#1140)