MOVIE REVIEW: Mank

MANK-- 4 STARS

The opening pre-credits prologue of Netflix’s Mank sets all the stages you need. Even if you have never seen the highly regarded Citizen Kane or are not well-versed in Old Hollywood history, you can understand the circumstances and implications presented. That crawl reads:

“In 1940, at the tender age of 24, Orson Welles was lured to Hollywood by a struggling RKO Pictures with a contract befitting his storytelling talents. He was given absolute creative autonomy, would suffer no oversight, and could make any movie, about any subject, with any collaborator he wished.”

Pull pieces of that out and put it in today’s context. Picture any big studio in 2020 issuing a blank check to an industry outsider born in 1996. Take a look at the list of current 24-year-olds. Remove Zendaya and Tom Holland because they come from, and are established in, the film business already. They don’t count.

You’re left with a host of YouTube stars, like David Dobrik and RiceGum. They would be the 21st century equivalent of a social influencer from another entertainment medium to the huge radio sensation that was Orson Welles before 1940. Who today gives someone like Dobrik any amount of money to make a Hollywood movie? Shit, the best he gets is a voice part in The Angry Birds Movie 2 and a judge’s seat on a Nickelodeon show.

LESSON #1: THE PROS AND CONS OF AUTONOMY— Keep going and look at the “no” and “any” tags in that prologue. That was a historic amount of leeway and creative freedom. Orson Welles teamed with veteran screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz to make an experimental movie that was a thinly-veiled expose at the largest media mogul of their day, William Randolph Hearst, who had the power to silence all publicity. RKO Pictures rode the lightning, diva and all with Welles.

Who today lets a David Dobrik-type have full say in making a film that would scandalize, say, Jeff Bezos, Donald Trump, Warren Buffett, Elon Musk, or Mark Zuckerberg and get away with it without lawsuits and nuclear heat? Ah, I see your raised eyebrow at that last name. I’ll wink back and say stay with me.

I can see you shaking your head from here. Exactly. It couldn’t happen. We live in a present time of cinema of nearly complete studio control. For example, just look at Disney’s tight grip on properties and image that has led to its share of creative differences and ugly separations.

There are nearly indestructible moguls today, no crazy prodigies like Welles with public favor to challenge them, and very few connected veterans with the balls of Mankiewicz to put any of it on paper. Well, it happened once, and it was Citizen Kane. How that masterpiece came to be is the stage to marvel when watching Mank directed by the accomplished David Fincher returning to the chief seat after a six-year hiatus from features after 2014’s Gone Girl.

Fincher’s film, birthed from a screenplay written by his late father Jack in the 1990s, chronicles two timelines for Hollywood screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, played by Oscar winner Gary Oldman. The present is him being bedridden at the historic North Verde Ranch in Victorville, California drying out and healing from a broken leg after a car accident. The digs are the ordered courtesy of the handsome commission Herman is being paid by airwaves wunderkind Orson Welles (BBC star Tom Burke) to write his auspicious movie debut in a mere 60 days. Assisting in this forced, alcohol-restricted creative isolation are the helpful housekeeper Frieda (Monika Gossmann of Iron Sky), the strict typist secretary Rita Alexander (Mirror, Mirror’s Lily Collins), and the blustering editor and Welles plant John Houseman (British TV star Sam Troughton).

The secondary threads go back to the earlier 1930s for little episodes of background on the people who would fill and guide Mankiewicz’s professional and social circles. Though a legendary mark for booze and and a lousy gambler, Herman was a top-paid screenwriter of regard for MGM, ruled with feigned benevolence and harsh shrewdness during the Great Depression by Louis B. Mayer (professional movie villain Arliss Howard) and Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley, son of Ben). The writer’s slippery wit endeared him to most everyone he met, including the platinum actress Marion Davies (Les Miserables’ Amanda Seyfried) who was the mistress of the media tycoon William Randolph Hearst (additional professional movie villain Charles Dance). Knowing her earned Mank and his wife Sara (Tuppence Middleton of The Current War) invitation and court jester status at the Hearst Castle compound in San Simeon.

What those typewriter-established flashbacks flesh out in Mank are the torn principles and burned bridges between Mankiewicz and the rich puppeteers above him. The straw that broke the camel’s back would come during the 1934 California gubernatorial election. The liberal Herman took increasingly greater offense at Mayer and Thalberg, bankrolled by Hearst, hiring actors to produce and release sham political attack films against noted author and Democratic socialist candidate Upton Sinclair running against their conservative Republican candidate-of-choice Frank Merriam. To the union man writer, that was a line-crossing use of clout and financial influence where “self-preservation is not politics.”

LESSON #2: TELL THE STORY YOU KNOW-- Herman was privy to the decadence that would inspire Charles Foster Kane. Oldman drops the telling line of “every moment of my life is treacherous.” He sat at those long tables, drank from those goblets, and benefited from their favor and systems with a smirk and a hungover shrug for too long. He witnessed the cutthroat deals, discarded values, and the greed that surrounded Hearst and his fellow connected elite that spread into the film industry. With an “I expect more of you” in his year, Hermon knows the risks in going against the brass. Like the old saying goes, “tell the story you know.” Those colorful and soured relationships filled Mankiewicz’s new American screenplay for Welles.

LESSON #3: THE DEFINITION OF “BEFITTING”-- The last word I’ll pull from that initial prologue to celebrate the combined merits of Mank is “befitting.” Short and sweet from the Collins Dictionary, “befitting” means “proper or right, suitable.” That’s the level of fascinating and respectful care given to this slice of silver screen history. It is inspired and vibrant for this movie to emulate the look and feel of 1930s filmmaking in every little component, through and through.

It’s the sound that grabs you first, opening with Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s smoky piano and strings that are far from their synthesized rock wheelhouse. True to the pre-stereo technique of the era, sound designer and supervisor Ren Klyce (Soul) stuffed all of the audio, including the dialogue, foley effects, set noise, and the score into one monaural track. There’s an authentic, warm feel to that level of balanced ambiance we haven’t heard for a long time.

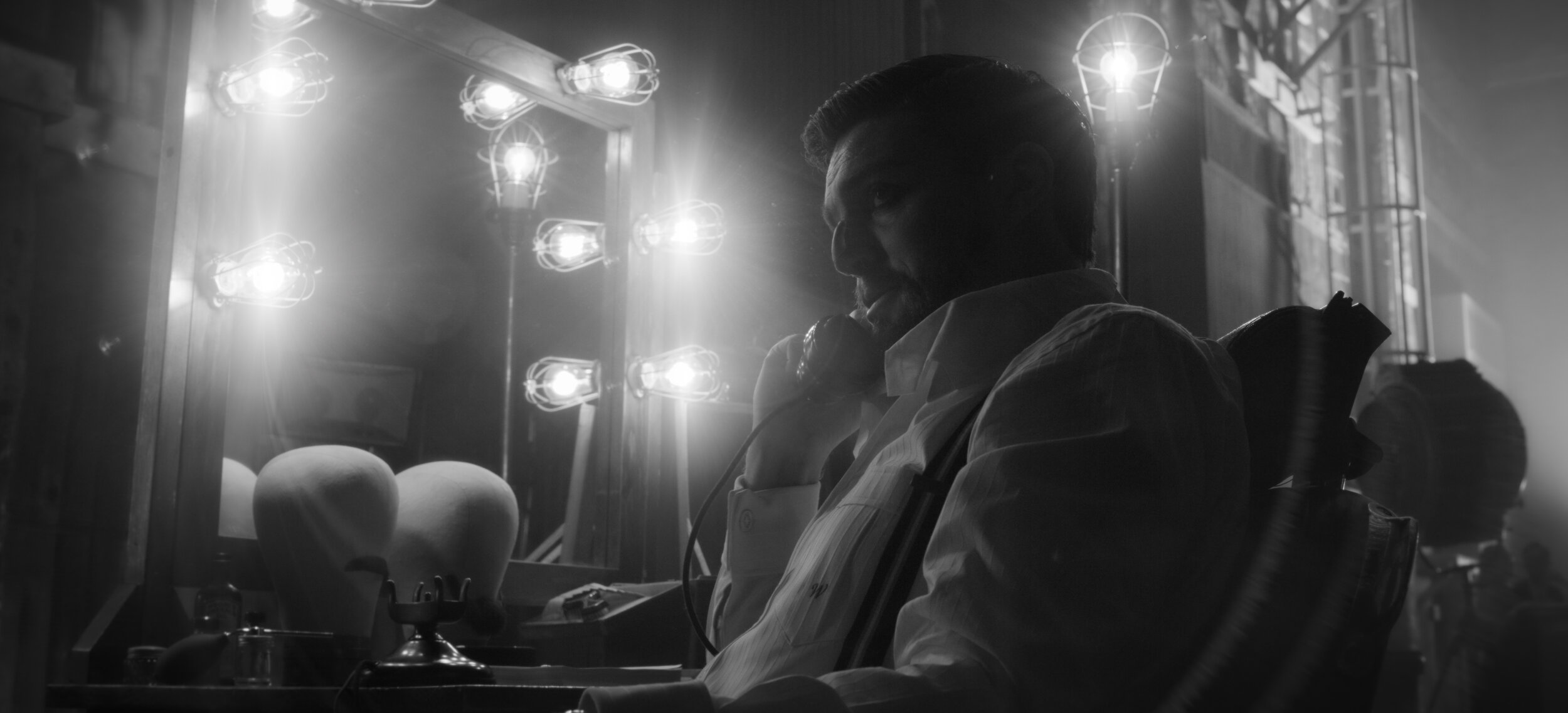

The intentional black-and-white cinematography captured on RED Monstrochrome 8K cameras occasionally plays with backlit noir shadows and deep focus techniques, kissing the ring of Citizen Kane’s Gregg Toland. Erik Messerschmidt, a promoted Gone Girl gaffer, was entrusted to shoot his first feature film and succeeds with an outstanding palette of tone for all of the gray areas of morals and virtues being toyed with in this seedy backstory. His light shines on the exquisitely recreated period sets and locations engineered and secured by the production design team headed by long-time Fincher collaborator Donald Graham Burt (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button). The same light compliments the lush costumes and gowns from costume designer Trish Summerville (Red Sparrow). All of those elements scream finery and stature.

All the same, it’s the bold barkers that provide the most stature of all. The portrayals of the hot-headed historical figures are veracious, starting with Oldman. One of the great chameleons, Gary bends playful panache into righteous indignation at the turn of a phrase. The film rarely ever leaves his side and headspace. Contending against him, Howard, Kingsley, and Dance create formidable presences and different concentrations of the topical political commentary within Mank that echoes from the history on display to our contentious present. Arguably, the scene-stealing performance of the film belongs to Tom Pelphrey of Ozark, playing Herman’s younger and soon-to-be more successful brother Joseph Mankiewicz. In a movie of loose talkers and big egos, he personifies the hard truths too few people say let alone hear. His scenes with Oldman cut hard.

While this may be Fincher’s spryest and most humorous film to date, Mank carries a self-importance that is not going to be accessible to all viewers. The dialogue isn’t quite the full rapid-fire of Aaron Sorkin, but not many lines and moments are given time to breathe and linger for effect. Fincher’s regular editor Kirk Baxter had the inevitable task of combing through hundreds of takes and a pendulum flashback structure to craft something curious and compelling. As gorgeous as it looks, this movie has its lulls.

Cinema aficionados, nonetheless, are right to have their Netflix queue ready for this homage December 4th. The semi-forgotten 1999 HBO TV movie RKO 281 starring Liev Schreiber and John Malkovich and, of course, Citizen Kane itself (spring for the Roger Ebert commentary as well) are recommended primers for homework. Couch surfers, however, aren’t going there. They are not going to be instantly impressed or inspired by an 86-year-old state election and little hints at the one big movie their film snob friends have demanded they watch for years. In many ways, Mank needed to be a gateway into the old conceits of movie magic for new eyes. That “suitable” definition of “befitting” may be its limit, no more or no less. Time and audience responses will tell.

LESSON #4: GAME RECOGNIZES GAME-- Come back to that wink I gave you earlier. Sports fans like to say “game recognizes game” when youngblood contemporaries hat-tip the greats in their presence or those that came before them. Thanks to The Social Network ten years ago diving into the not-so-nice history of Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook, David Fincher knows this Welles-Mankiewicz territory all too well. He put a bullseye on an emerging institution and enlisted the wily Aaron Sorkin to help him light the fuse. Mank is a stylish tribute to courage that came before him. Fincher gets it. Call Mank “balls recognizing balls.”

LOGO DESIGNED BY MEENTS ILLUSTRATED (#925)