GUEST ESSAY: Architecture and Animation with "Howl's Moving Castle"

Architecture and Animation

By Terrance Steenman

To be honest, I never thought too heavily about architecture growing up. I imagine most people feel this way their entire lives. Sure, when we were children there were LEGOs or Lincoln Logs (if you were so fortunate as to have those toys), and with those toys one could build a space of imagination, but rarely do people make the connection that the lessons learned can be applied to the masonry, wood, steel or concrete that shape our daily lives. Constantly in the field of architecture, we are told to think back to a time when we did not have architectural eyes, and to instead view architecture from the lens of the ordinary person. Often, I think of this time as coinciding with my childhood and thinking back so often I remember with some accuracy that period of my life. That state of mind, simply being and not analyzing the architecture I was in. Obviously, it began when I was born but strangely ended later in my teen years, and I believe that watching animation and cartoons was one of the factors. Now, you may be curious as to why this was the case and why this is one of the catalysts for my architectural eyes and thought but honestly, I am surprised why this has not been the case for more people.

First, the medium of animation is not all that different from the realm of architects. After all, each frame in traditional animation needs to be hand drawn, and every line has a singular purpose: to sell an idea. Every person, building, and object of animation is not simply recorded in the same way standard film is recorded. To get a simple shot of a busy street, one must just find and record one with a camera, but in animation often there is not even a video camera in the process at all. Every frame has a unique purpose to aid in the story, not just every shot, and to not include even the most mundane context has to be a direct consequence of the design of that frame. Just like architecture, the animator must design and fabricate a set of drawings in such a way as to give meaning to color and ink that is on the page and must use that meaning developed to tell a story or otherwise provide purpose. It is a testament to this ideal that we treat animation as having gravity, air, and many of the things that our own reality has, but none of this is true. In actuality, the story and universe that is built in animation only exists in our minds.

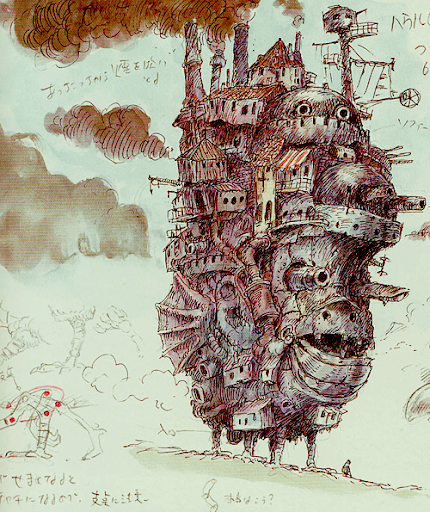

Figure 1

Figure 2

Now that we understand the medium, the second point is in the drawing of animation itself; more accurately the backgrounds that are created. The shots are drawn in such a way as to show the world that surrounds the main characters, and that they fit within a larger context; much like how real stories fit within the context of reality. Without the background many animations would lose meaning, but with it the story can become greater and provide more meaning than the script alone would allow. For instance, in Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle, the soldiers, customers, hatters, and people of the city are drawn even when most do not interact with any main character in any way. These additions to the page and consequently the background seek to immerse the viewer in a world and get the viewer to buy into the narrative and thus be pacified by it. To continue, Miyazaki turns this into an art form itself, constantly having the characters he creates interacting with the environment in more ways than traditional animation allows. The smoke makes Sophie cough, leaning against buildings, tripping over objects, even the wind making his characters cold. Often these little tricks are serving no other purpose than to interact with the characters drawn and to immerse viewer into his work. This is the architecture of Studio Ghibli. Of course, a set is required much like a building, but drawing it in this way brings the backgrounds to the foreground. The set causes the viewer to be made aware of the surroundings and context of the scene. Once made aware, little gems of interaction can be found anywhere for those willing to search. Simply details exist for detail’s sake. It represents a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) and much like its predecessors of animation even voices and text are there to carefully aid the story with each subtle piece fitting to balance and seamlessly integrate into a larger whole.

Figure 3

The architecture of animation is unique in its process of creation, but much like architecture it has several layers of design. Chief among them is the story or plot. It is the structure of the film that ties each event into another and progresses the story forward, but like architecture, it requires a plan. Plots and subplots have to be created to progress the story forward. Characters have to be given a back story, personality, goals, as well as idiosyncrasies, fears and the like, to make them rounded and grow throughout the events that unfold. Settings have to provide meaning, and chapters have to show how the characters interact in such an intricate way where the audience is immersed as well as understands what is going on. Everything has to be woven like threads on a loom to make the fabric of a narrative; similar to the layers of the design of a building that have to be orchestrated for it to blend seamlessly into the background of everyday life. To talk factually, animators use rising action, plot, narrative, and characters all tell the story, but these things are often worked out before the story is even created. When creating a story, it is often assumed that a writer or animator would sit at a desk and just start writing; but that is akin to a builder just starting to build. A narrative, much like a building, has to be planned before it is constructed; scheduling where each part can be added to create the story that becomes a beautiful work of art. Now, what is interesting about the example I gave before, the story of Howl’s Moving Castle, is that it has been crafted in such a way twice. Once for book form, but again for the movie, with both animator and author being at the top of their craft. This leads to little things that cannot be even described when the story is created of Howl and Sophie, but it is generally understood as the human subconscious understands it. It takes a fraction of a second to understand that every second of this film has been meticulously constructed to show the theme and the message that Miyazaki wants to portray, and that is why this film is recognized as one of the best in the business. Not because of its plot or even its narrative but because all aspects of the writing and animation seamlessly blend together. If the film is architecture, the idea that ‘less is more’ is not followed, rather—it is the details that make the world of difference.

Now, let’s take a deeper dive into Howl’s Moving Castle and what it portrays in its animation of architecture; more accurately, the castle itself. When first entering the home, Sophie is greeted by a dirty and poorly kept interior (obviously neglected). Deciding to take a nap, she is greeted by the fire named Calcifer who is metaphorically and literally the hearth of the home. He boils the water, moves the castle and is generally responsible for being the house itself. The house does not exist without him along with all its magical properties. He is the house. What does this imply about the issues discussed? I note that this is the view Miyazaki, an animator, is trying to express about architecture. That all houses have a fire, or center (not always physical), but one that is often expressed in the people that occupy the space. Further, much like Calcifer, the home that you make, and its richness are determined by how much effort or part of yourself that you put into the space. If only a little effort is put into the home will it will not become fully utilized, but if it is clean and live in the space it become something more. Calcifer, and thus the house become a reflection of the characters; he is the foil of Howl and Sophie. It is what allows us to know what the characters are thinking and without him the whole subplot of Howl’s war efforts and its toll on him would be lost. Now some are thinking, “Wait, can architecture be all that; a foil or comic relief in daily life?” Simply, yes. In fact, that is the very role architecture plays in all our lives. It is the foil of our individual stories and we interact with it more than humans in order to fulfill our goals. Without architecture, the story of our life would have very little context and the context would change so often (with the weather) that the world would become foreign again. As far as architecture being expressed as comedy, one must look no further than the classic films of Mon Uncle and Playtime. Although they are not animation both films provide countless laughs from purely situational comedy that riff of buildings and how they are currently designed. Generally, what must be understood is that even though Calcifer is a fictional character, his ideas and role fulfill the ones completely necessary for a house to fulfill. Howl’s Moving Castle is an animation of architecture. Furthermore, all animation can be viewed as a nonstandard reality or fake representation, but it is in that parallel reality that we are able to more accurately reflect on our own.

Figure 4

Now we have talked about the animation of architecture and the architecture of animation and thus it is important to understand that these two fields are more closely related then distant when viewed from the larger lens of creativity. Be it an animator or a principal that runs the studio, the process is crafting big projects of creativity, and the final result is drawn. Few differences are found, and the only real difference is that animators’ drawings are imagination while an architect has drawings of planned reality, but then again maybe not. The great architects often go beyond reality and into architecture theory, crafting buildings that cannot or will not ever get built, but still the ideas conveyed are celebrated. Therefore, it is important to assert that the films created by Studio Ghibli and all animation are in fact at some point a version of architecture theory in and among themselves. Not in the traditional sense of architecture theory, but much like commonly accepted great buildings they represent a clear message and typology of culture and its many facets. They are vignettes into a reality that could form a different realm and how the world could be distinct because of those minor tweaks. As we look back into the animation of our past, it is important to understand this possible lens and where it might take us, not just in these films but in all architecture in general. Animation and architecture are not too different and have been close cousins of creativity all this time. All in all, it is important to understand the lessons that the world teaches us about architecture. First, we learn from toys to take imagination and apply it to reality. Additionally, we must learn for animation and how to take design parameters, much like air and gravity, and ingrain them into our work so much that you cannot conceive of the individual lines on the page, only the idea of the drawing which is created.

Figure 5

Bibliography

Miyazaki, Hayao, Toshio Suzuki, John Lasseter, Rick Dempsey, Ned Lott, Pete Docter, Cindy Davis Hewitt, et al. 2006. Hauru no ugoku shiro = Howl's moving castle.

Jones, Diana Wynne. 2009. Howl's moving castle. London: HarperCollins Children's.

Ede, François. Playtime : [Un Film De Jacques Tati]. [Paris] :Ed. Cahiers du cinéma, 2002.

Ede, François. Mon Oncle: [Un Film De Jacques Tati]. [Paris] :Ed. Cahiers du cinéma, 1958.

LOGO DESIGNED BY MEENTS ILLUSTRATED